It’s cold outside. The furnace is running. When the temperature indoors at the thermostat first exceeds the set temperature, the furnace shuts off. The indoor temperature slowly falls to below the set temperature, then the furnace kicks in again. The one-degree F temperature drop takes about ten minutes. Now, suppose the temperature drops fast, say 5 degrees in just a minute or two. What do you do? Call the furnace service person? If you did, she’d probably tell you to shut the damn door. Not a furnace problem.

That’s what I was thinking about last year during an overnight hospital stay for pneumonia. They had me all hooked up to monitors. The oximeter on my finger, which reads peripheral blood oxygen saturation (SpO2), gave an alarm in the middle of the night, reading 75%, down from the desired high nineties. The wonderful care team recommended I get a sleep study for sleep apnea because, they said, a drop in blood oxygen like that (hypoxemia) must be due to stopping breathing—obstructive or central sleep apnea. So what did I do? I did what any reasonable building scientist would do—I started holding my breath, and then hyperventilating, to see if I could jimmy my blood oxygen saturation down or up. And I couldn’t.

If you are reading this blog post for medical advice, stop right here. If you have a building problem, give me a call. If you have a medical issue, go see a doctor. If your doctor tells you how to size a heat pump, you’re in the wrong office. If you’re thinking I have any medical advice to offer you, you’re reading the wrong blog. Is that clear? The remainder of this post is about me, not about you. Let’s continue.

The issue here is rate of change. We can model any process, essentially writing an equation for that process, and that equation will have a derivative that expresses the rate at which the function…well…functions. Heating and cooling a closed-up house changes slowly. If a rapid change occurs, something besides the furnace is in play, like an open door or window. Holding my breath, or hyperventilating, led to very slow changes, if any. My hypoxemia was due to something other than apnea, some kind of door or window opening, I was sure of that.

But I followed the advice I’m giving you here—go see a medical specialist. Normally I like doctor’s offices. Most of what I know about anatomy I’ve learned there studying the charts provided by various vendors after getting prepped. Not at this sleep specialist’s office. It was cold and bare except for a shelf of styrofoam skulls wearing CPAPs. I quickly learned that I was not in the office of a multi-dimensional, multi-disciplinary garage mechanic who listens to nuances of sound and feel, no, I was at Apnea-R-Us. My research project is n=1 (number in the study population), and they have the world to study. I am quite sure they have provided great benefit to wide populations. We just weren’t on the same wavelength. Also, I’m a gold-medal sleeper. Apnea leads to sleep disorders; I don’t have any of those, so I figured I can make a science project of this, while most apnea-sufferers cannot.

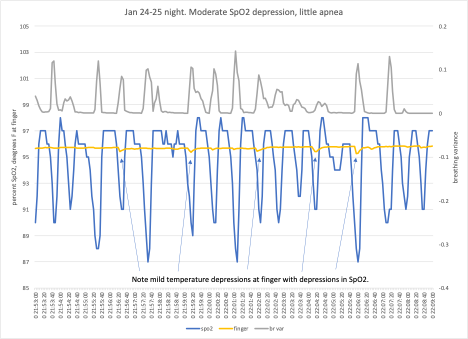

I purchased two recording pulse oximeters and measured my SpO2 at night, over many nights. (Why two? Ask an aviator.) I found that during a normal night—for me—I would get usually two clusters lasting about 20 minutes each, during which my SpO2 would spike low, usually below 80%. The rest of the night was pretty uneventful. The readings on my left thumb matched those on my right thumb maybe 70% of the time, but for the remainder they differed a bit, in pattern or in magnitude. This helped confirm my suspicion about that elusive something else.

I wanted to test to see if I have apnea. So, like a good building scientist, I bought an old-school blood pressure rig, with an inflatable sleeve, bulb pump and dial manometer. I duct-taped the sleeve to an old T-shirt. I hooked up the tubing to my blower door micromanometer, and coupled that to my old Campbell Scientific datalogger. And went to sleep. The sampling interval was less than ideal with the manometer, but I came away with data showing that my chest never stopped expanding and contracting all night long. Later I learned that most people with apnea have obstructive sleep apnea, during which the chest keeps pumping like normal, but breathing is blocked at the windpipe. During central sleep apnea, the brain tells the lungs to stop pumping.

Then came the night all wired up in the sleep lab for my polysomnogram. I surreptitiously slipped my two pulse oximeters onto my thumbs, for calibration, but also to keep the sleep team honest. Uneventful night except I had dreams about doing a sleep study.

I received a two-page summary which showed, among other things, that I had 140 obstructive sleep apnea events, or 29.6 total events per hour, which meant I had moderate sleep apnea, but was just under the 30 per hour threshold of severe sleep apnea. I requested an electronic copy of my polysomnogram. I was sure that I could find my hypoxemia trigger in there somewhere. No, they said. Yes, I said, and pointed to the relevant sections of the HIPAA act. No, they continued. I contacted the vendor for their sleep apparatus, the first time they ever had a patient rather than a medical professional contact them. When you do building research you get mighty good at squeezing essential information out of tech nerds on the phone. I got a copy of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) Scoring Manual. So the clinic sent me the 3 Gigabyte file in .edf format, a European binary format. My daughter, a PhD neuropsychologist, provided me an .edf reader. I read the file. I compared their scoring to the required scoring methods in the manual. Their notations were garbage. Total horseshit, random assignments of event status having absolutely no agreement with the apnea that I actually did have. And, boy, did I have apnea. I notified the sleep clinic about their flawed summary but they didn’t seem to care and frankly neither do I. I’m interested in hypoxemia triggers, not gotchas for well-meaning but perhaps lazy providers of essential medical services.

But let’s back up a bit. Research begins with a literature search, and such searches usually begin on the internet. Here’s what you read about the apnea-hypoxemia nexus on the first few pages of a search. Oxygen is good. Breathing is good. Interrupting breathing—apnea—is bad. Interrupting apnea—CPAP for example—is good. Got apnea? Get CPAP. We’re done here. Not quite that bad but almost. I could find nothing about sleep hypoxemia that didn’t attribute it to apnea. I’m not surprised. Having studied building research for the last 80 years, I am well aware that the justification for research is the development of standards and guidelines and protocols that will improve lives. Once those standards and guidelines get adopted, the quality of any remaining research takes a nosedive. Guidelines may improve lives but they kneecap research. Society has made an investment in a building practice, and future research which might question or challenge the adopted practice is treated like a stinkbomb. Radon under 4 pCi/L. 1/300 attic ventilation. 50% RH in museums. Don’t go there, research is not welcome. Would anyone in their right mind question the link between breathing and oxygen saturation measurements in the blood?

I wanted to get a baseline to see to what extent apnea—in this case intentional wide-awake apnea—would lower my blood oxygen. I held my breath for 23 seconds during each 60-second interval for 15 minutes. My blood oxygen did not decline at all, including 10-minute still time before and after.

So I decided to do my own “polysomnogram”. I adapted a nose-breathing tube with a thermocouple to measure nasal temperature. I love thermocouples. There is no simpler and smaller instrument than a simple joint between two dissimilar metals, exercising the electromotive Peltier effect of temperature dependency when dissimilar metals come in contact. I set the datalogger to measure at 4 samples per second—fine to capture breathing patterns. I got good results. Here is what I found.

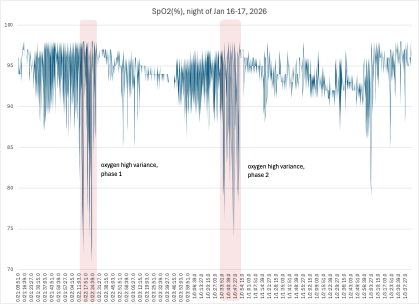

First, this chart shows that I had two clear clusters of hypoxemia spikes during the night. We will focus on those.

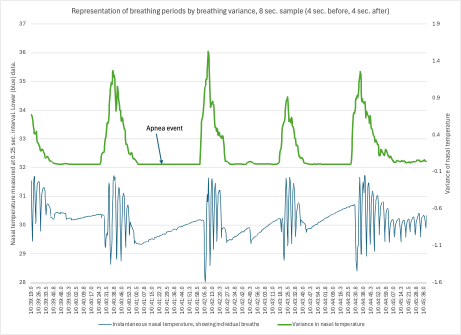

I wanted to find a way to distinguish periods of breathing from apnea periods. I did this by taking the variance in nasal temperature readings—the variance over a period 4 seconds before and 4 seconds after the sample time. Variance is a standard statistical measure of the non-uniformity of a data point compared with its neighbors. A high variance meant I was breathing, a low variance showed that I was not—an apnea event. In the chart below, the thin blue lines were nasal temperature indicating individual breaths; the thicker green line, the variance at that point.

Note to sleep specialists trying to accurately score sleep events: it’s easier with this variance conversion because it is easy to distinguish the correct starting point which occurs when the sleeping variance reaches 10% of the variance during breathing periods.

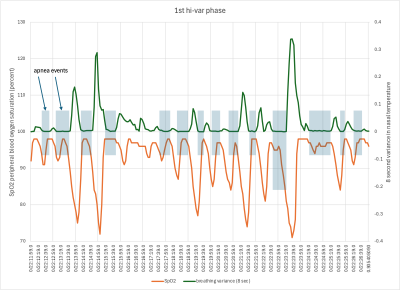

Let’s take a closer look at the two periods during which I had hypoxemia spikes. First one:

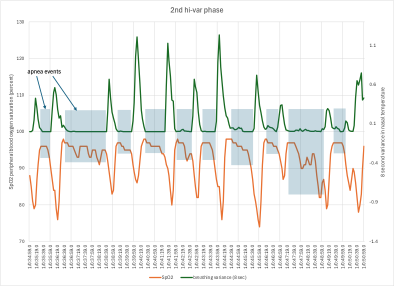

And second one:

Lessons learned:

- Yes, there is a relation between apnea and hypoxemia—they both occur (for me) during these cluster times, but

- The hypoxemia events occurred during breathing periods; during apnea the peripheral blood oxygen saturation remained high, though a slight decline is evident.

The rate at which peripheral blood oxygen saturation falls then rises again is too rapid to be explained by respiration alone. It’s almost as if a gate closes stopping blood flow to my periphery, then opens back up again, and it only does this while I’m breathing. Is there such a gate?

Well, yes, there is. Pre-capillary sphincter muscles are gates that are capable of permitting or restricting flow from arterioles into capillaries. I find papers describing their role in the brain, but not elsewhere in the body. I’m still looking. Here is a hypothesis:

- Apnea occurs. Perhaps it is just an unfortunate blockage that occurs when the back of the tongue collapses into the trachea, which the body is then called on to accommodate (or not). Or perhaps it is a natural normal occurrence, as might be suggested by seeing how breathing strength diminishes over a half-dozen breaths prior to the apnea event, as if it foresees apnea. Open question.

- Apnea certainly will not add oxygen to the bloodstream. Oxygen is added in the lungs; lungs get first dibs on oxygen, saturating the blood to the arterial blood saturation level (SaO2). Next comes the heart. Then the brain, all nourished with arterial blood. The pulse oximeter on my thumb is pretty far downstream from the primary organs of the body.

- Perhaps in order to maintain high SaO2 levels during apnea, a signal is sent to the periphery to close the sphincter muscles, not for long, and not during apnea.

- The drop in blood oxygen saturation is rapid, but somewhat slower than the subsequent rise. If the periphery circulation is closed, the finger consumes the blood oxygen that is in place. When it reopens, the fresh blood re-enters quickly.

Can this hypothesis be tested? Well, yes, it can. If blood is turned off to the thumb, then the temperature of the thumb should drop and the blood oxygen concentration should drop. How much would it drop? We could contact Crime Scene Investigators who seem to be specialists in determining a time of death (stopping blood flow) from body temperature. Or, I could imagine navigating a labyrinth of hospital protocols, and gain access to the oximeter redadouts of a patient who died. Fat chance of that. But remember, I love thermocouples, so I measured it myself.

Sure enough, the finger temperature drops coincided with drops in peripheral blood oxygen saturation. That’s where I’m at. I think pre-capillary sphincter muscles do appear to play a role during sleep that helps accommodate the occurrence of apnea, helping to ensure sufficient oxygen for vital organs.

My sleep specialist kindly provided me with a reference claiming to show that people with apnea are associated with greater risk for heart disease and stroke. As a researcher, I’ve learned that “associated with” represents the weakest claim on causality. I must go through that literature, as anyone concerned with this issue must. And I approach it with my normal skepticism. What is a subject “with apnea”? Apnea, by the AASM definition is perfectly normal if fewer than 5 events per hour occur during sleep. Are the subjects diagnosed then treated, and if so can the researcher distinguish risks arising from the underlying condition, not the treatment itself? How many wierdos like me can they find with an apnea condition who choose to defer or delay treatment? Is the risk proportional to the apnea severity—ranging from normal to severe? I don’t know, but I appreciate the importance of pursuing answers.