I have often been asked, regarding my book Water in Buildings, what is the main takeaway. In response I told the story (it’s actually apocryphal, sorry, Eric Werling) that a student came to me and asked if I could summarize the book, and I said, yes, I could, in fact I could do it in four words. (Four words? Yes, four words.) “Cold-wet. Warm-dry” with the links in the pairs being stressed. I followed this by saying that if you lose track of what is linked with what, then go do your laundry. Cold things tend to be wet, warm things tend to be dry.

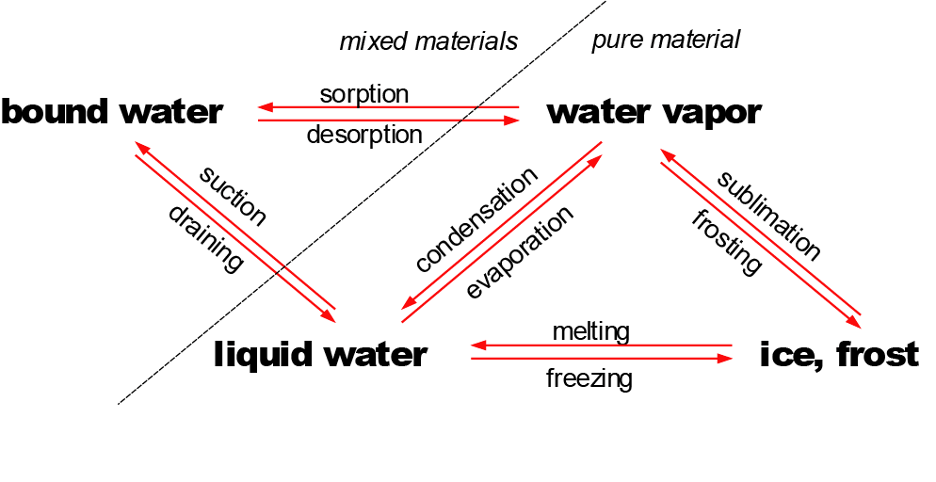

There’s a more fundamental point which I covered in the book, namely, bound water. Pure water has three (common) phases—vapor, liquid and ice. But what interests us in building science is, actually, impure water, dirty water, water that is somehow bound up with other material, like water in a sponge, a block of wood or a brick. Water is a polar molecule so it forms hydrogen bonds with itself (cohesion) and with other surfaces housing unbalanced charges here and there (adhesion).

I didn’t go into great detail about the micro-microscopic details of what those attachments are like. The molecules directly adhered to a charged part of the surface will be most tightly bound, but a charged surface with one layer of water molecules is still charged, slightly less so, and so there is a gradient of bonding as we go from the most tightly held layer outward to the free water, unaffected by any charge in the surface. A mobility gradient. How far away from the charged surface does the mass of water “feel” the pull of a hydrophilic surface? 3 molecules? 3 million molecules? Hmmm…

A little refresher regarding units: A millimeter (10-3 meters) is small, about 1/25 of an inch. A micrometer is a thousandth of that (10-6 m), a nanometer is a thousandth of that (10-9 m). A nanometer (nm) is about three water molecules across. The surface roughness of float glass is 50 nm or less, so two glass plates sandwiched together leave elbow room for maybe 300 water molecules to pass between without pushing the glass plates apart. Forget Inch-Pound units for this discussion.

Molecules have energy, a leftover from the big bang. The energy gives all of them rotational and vibrational energy, and it gives to fluids—liquids and gases—translational energy as well. They move. They have velocity. They collide with one another and with the surfaces that contain them. Gases have the highest energy, lower for liquid, and lower still for solid water. Is bound water a solid or a liquid? Well, it is partly immobilized by the hydrogen bonds at the surface and away from the surface, but molecules that are locked in a bond may be released from that bond in the next nanosecond. You might say that along with the mobility gradient (lowest mobility right at the surface, highest in the mass of the water) there is an energy gradient. The bound molecules lose some of their translational energy—some, not all, more right at the surface, less farther away.

Years ago someone showed me a fascinating infrared video. A weatherization professional was doing an IR scan of an interior room when a rainstorm came up. The rain splashed against the patio door and began to run into the room under the door and onto the carpet. And as the water front moved into the room, the edge of the water glowed bright in IR where it was absorbed by the carpet! The line glowed bright and moved into the room showing the advance of the liquid water.

I live in Urbana Illinois. We’re not famous for mountains or beaches or movie stars. What we do have in town is Nobel Laureates. Tony Leggett is one of them—he discovered superfluidity. We also have a local farmers’ market, and even non-farmers may have a booth. Tony Leggett set up a booth, just a table and a plastic tent and a sign inviting people to ask physics questions. So I went and asked for his explanation of this phenomenon which I described. He had to think for a moment, but he was pleased to find a visualization he hadn’t encountered before.

Well, I’ve lost track of that video. So I did my own, in order to illustrate that the phase change from liquid water to bound water involves a loss of the water’s energy, and so the lost energy has to be given off as heat, and the reaction is exothermic. Here is the result. I am not seeking to be quantitative here, only to show that the reaction is indeed exothermic, and bound water is clearly at a noticeably lower energy state than liquid water.

What does the mobility/velocity/energy gradient look like? My search engine skills leave a lot to be desired, so I decided to figure it out for myself.

As with any problem, we begin with what we know. We know the surface tension of water. We know that water adheres, not very strongly, to glass. We’re all familiar with the little curl upward that a water surface makes against a vertical glass surface. We know how to calculate the rise of water in a capillary tube.

In a mass of water at a given temperature, there will be an average energy for the molecules, while the individual molecule will have varying energy according to the Stefan-Boltzmann distribution. In a mass of water, unaffected by any charged surfaces or particles, the average energy will be the same, whether the molecules are at the surface or below. So their attachment effort will be the same. Molecules in the mass attach up, down, left and right, while molecules at the surface attach left, right and down, but not up. To even things out, they attach left and right more strongly. This stronger attachment at the surface creates a “skin” although a “skin” analogy is flawed. In one dimension, it’s as if you have a rubber band that requires a force to pull on it, but the force remains the same regardless of the length of the band. This is a rough description of surface energy or surface tension (s). The units are Joules/m2 which is equivalent to Newtons/m. The surface energy of water at room temperature is s = 0.073 J/m2 which is the same as 0.073 N/m or mN/mm (milliNewtons per millimeter).

Suppose you have a capillary tube, and pure water climbs up the tube because glass is slightly hydrophilic, inviting water to attach to it.

Sometimes you hear this discussion turning to capillary rise of water in the xylem of trees. I hate it when they do that. A glass capillary tube has air at the top which limits its rise; if the glass tube was filled with water and stoppered at both ends, the rise of water in the tube could be anything you want. Trees don’t have air in them. If they did then any leaf more than a few feet off the ground would go begging for water. How did water get up so high in a tree? It’s been continuously in there, without air, from day one. Nutrients travel by diffusion.

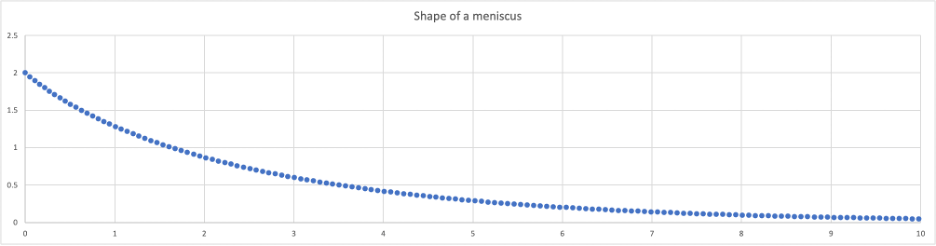

The attraction of a surface to a liquid shows up in the meniscus. Adhesion of water to glass is greater than cohesion of water to itself so water climbs in a capillary, and the water surface edges point upward. Mercury, famously, has stronger cohesion than adhesion so its surface edges point downward. A liquid with no adhesion to the surface would sit flat. The strength of adhesion thus shows up as an angle (q) of the meniscus where it attaches. The cosine of that angle represents the strength of the adhesion.

Here’s how to calculate the rise of water in a glass capillary. There is no single value for the cosine of the adhesion angle. There are no angles at the molecular level. Impurities and irregularities will always be there. So let’s say 45 degrees. Then an upward force attracting water of s*cosq is applied all along the attachment. In a capillary tube, the length of the attachment is the circumference of the opening or 2pr where r is the radius of the tube. That’s the upward force that is balanced by the lifted weight. The weight is the volume (area x height) times the density (times acceleration of gravity to convert mass to weight). Homework: calculate the height as a function of the radius.

Now, let’s calculate what the shape is of our little upward flip of water where it meets a vertical plate of glass. The upward force along, say, 1mm of length must equal the weight of the total water lifted above the water level reference line, in a slice 1 mm wide. The upward-pulling force is s*cosq*1(mm). At 45 degrees the adhesive force of our slice can lift 0.05 mN, which must equal the weight of the water above the flat water surface. The values in this chart are derived from a sequential calculation assuming 1) tension is uniform along the meniscus, and 2) height of the meniscus is proportional to the cosine of the angle at that point. Explicit solution to the meniscus equation? Beyond me, I had to look it up. You may too.

Why is this important? It is part of an investigation into the likelihood—or not—of freeze-thaw damage to stone. There is a body of literature regarding crystallization pressure, which focuses on the very thin interface between a surface and an ice crystal growing toward the surface, and how that thin film of water may reach pressures in the 10s of megaPascals, high enough to rupture stone. That’s the claim. I see a half dozen problems with that claim. But here I just wish to point out one, which lessens the rate at which water molecules between two very close surfaces can feed a growing ice crystal.

When water is adhered to a (hydrophilic) surface, a mobility gradient occurs, with most tightly bound water molecules adhered directly to the surface. The molecules become more mobile at distances away from the surface. The curve of a meniscus represents this relative (im)mobility.

Leave a reply to watersmiths Cancel reply