I love how architecture is described as a marriage. It’s a marriage between, what exactly? The sacred and the profane? Form and nature? Spiritual and mundane? Art and craft? As a building scientist I know exactly which side of the bed I sleep on in each of these pairings. I ought to have at least a passing acquaintance with “my better half”. I’m a building scientist, and these matters of genius and spirit don’t lend themselves to science investigation—inductive or deductive. So here are some of our encounters.

Earlier I riffed on Browning’s poem “Andrea del Sarto”, that looked at artistic genius from the craftsman painter’s viewpoint. The main point of that post was that craft training proceeds slowly, through stages, maybe reaching mastery largely through the perspiration side of the perspiration/inspiration duo. But how does genius arise? In grad school I was told that Gropius said that architecture must move “beyond competence”. OK. Does it do that via competence, or does it do it by leapfrogging the grinding quest for serial modest improvement? The audience of publics and critics learn to appreciate the appearance of genius, but how do those of us in the racket actually deliver genius? Artistic genius seems low on the transcendence scale, a gateway drug perhaps. But it has that quality of unplanned and unscheduled appearance. Genius gets the goodies. Should I be jealous?

I remember a talk years ago at the School of Architecture given by E. Fay Jones. He presented his Thorncrown Chapel in Fayetteville AR. His presentation consisted of a litany of all the thesaurus synonyms for the word “spiritual”. The next morning I met with my young research assistant for his reaction. He said that there was nothing spiritual in the work because it did not arise from devotion to his Lord and Savior Jesus Christ. He has a point there. What is spiritual to one person may not just be non-spiritual or mundane to another; it might be downright anathema. That’s the spirit world for you, as transcribed throughout history and anthropology; the stone which is an altar for one community is just a rock to their neighbors, inviting itself to be knocked over. If we invoke the nether world to help infuse our work with the sublime, a lovely bosomy goddess may appear. Or a screaming banshee. You just never really know.

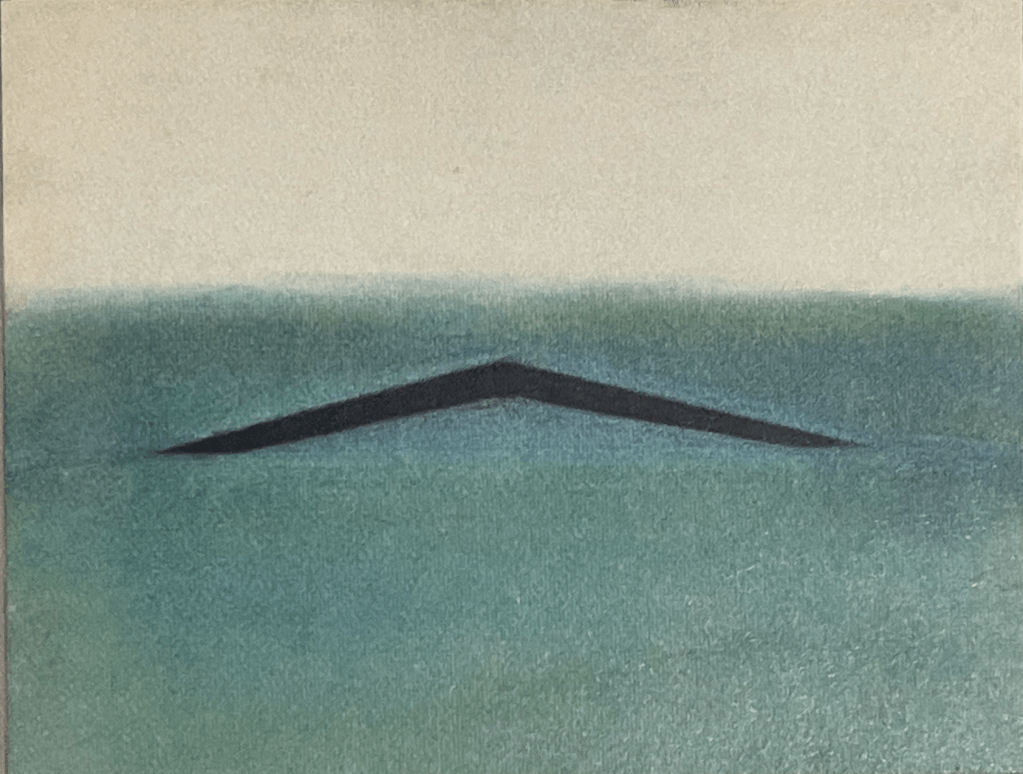

I am of the generation touched by the war which the Vietnamese call the American War. My own involvement? Felony conviction, we’ll leave it at that, but for a decade afterwards I led a furtive, unhealthy life on the margins, doing construction. Following that I went to Architecture School, at the GSD. In the summer after my first year, I was paging through Progressive Architecture, and happened upon a small blurb showing a smoky landscape with a black V carved into the soil. Maya Lin, student at Yale, had won the competition for the Vietnam Veterans Memorial. I thought: This is it, this is it, this will remain, this is a keeper, this is my keeper. Some future armageddon tsunami of wind-rain-fire could come and wipe all the architecture away, all that phallic shit, but this will remain. It protects, it protects the names, our names. The earth opened up, swallowed 59,000 of my compadres, then closed up again. This would be a fitting monument for the Vietnamese who died, though it would have to zigzag across the whole DMZ. I was the luckiest person to be on this side of the wall and not on the other. I imagined asking some buddy, one whose name would be chiseled on the wall, what are you doing in there; and he would answer, as Thoreau did to Emerson from his jail cell during the Mexican War, what are you doing out there? There are not many pages of architecture journals wrinkled with an hour’s worth of warm tears, but I know one. A year later, I was TA for a structures class, correcting Maya Lin’s grad school homework. The memorial dedication took place over Thanksgiving break. She did not return. I asked what happened. I was told that she had no role at the ceremony, and that she and her parents had been treated to the slurs my generation had concocted to insult East Asians. I hope to hell that isn’t true. I never introduced myself to Ms. Lin. I still don’t know what I would say to her besides thanks. Is there something special, something sublime, something transcendent in the slabs of black granite covered with names? I’ll never know. For me they are evocative, as they seem to be for my contemporaries. It touched a spot deep in me, a spot with fear, a spot loaded with hurt. That’s all.

Is wonder transcendental? Where the work seems to require something far more or greater than building science can imagine. The pyramids. The temples of Angkor. The Inca stone walls. Such achievements appear out of range for us. I remember one summer in the 60s working as a laborer on the C&O canal in Washington DC. Part of the towpath side of the canal had washed away into the Potomac. I recall hearing the engineers saying they could not get the compaction with their equipment that the original builders got with mules. Previous posts here discuss astonishing achievements of prehistorical technology that requires us to imagine only that things we consider rare—mercury and diamonds—were more plentiful back then. So, our own limitations should not be taken as a measure for distinguishing what is physical from metaphysical.

You can always ask the experts. One person who claimed expertise was the historian of religions and colleague of Carl Jung, Mircea Eliade. I do not recommend his work, nor his personal or political direction. A reader gets no sense of who his subject people and cultures are, only how they fit into outlines of his own devising. (To feel you are actually part of history before history, I strongly recommend The Dawn of Everything by Graeber and Wengrow.) Let me provide a quote from Eliade’s The Sacred and the Profane for two reasons.

We have seen the cosmological meaning and the ritual role of the upper opening in various forms of habitations. In other cultures these cosmological meanings and ritual functions are transferred to the chimney (= smoke hole) and to the part of the roof that lies above the “sacred area” and that is removed or even broken in cases of prolonged death-agony. When we come to the homologation cosmos-house-human body, we shall have occasion to show the deeper meaning of breaking the roof. For the moment, we will mention that the most ancient sanctuaries were hypaethral or built with an aperture in the roof — the “eye of the dome” symbolizing break-through from plane to plane, communication with the transcendent.

The first reason I provide this quote is that it captures the idea of transcendental-as-hokum, an idea we should never lose sight of. The second reason is that it provides celestial justification for ventilating your attic. To find out whether attic ventilation is actually hokum or not, please visit the posts on this blog related to that topic.

Is there a personal enlightenment available through this marriage of the divine and the ordinary we call architecture? In the film Indecent Proposal Woody Harrelson plays a struggling young architect and Demi Moore his devoted young wife. Robert Redford comes along with his yacht and offers Moore $1 million if she’ll sleep with him. Woody and Demi scoff at the idea, but over time the no becomes a yes, and the young pair promises one another they can handle it. They can’t of course, so they split, and Woody buries himself, not in architecture but in architecture teaching. He lifts Louis Kahn’s lines about the wishes of bricks; he becomes infused with the spirit, and he infuses his students. The camerawork takes a psychedelic crescendo, and his standing bursts above the worldly, achieving the one thing—design divinity?—that can make Demi ignore Robert’s riches. Woody Harrelson becomes transcendent. Or whatever.

I’ve been assured that personal enlightenment, or satori, is available through intense single-minded concentration combined with personal deprivation. While charretting as a student all I got was tired. When my mind drifted from the boards that looked menacingly empty, I wondered if other professions produced inspired work through deprivation. Dentistry? Truck driving? Air traffic control? Later, in practice, I was struck by the calm rectitude and inscrutable gaze of the mechanical engineer; I figured it must be due to long meditative sessions spent with that most endearing of mandalas—the psychrometric chart.

Is architecture a priesthood, mediating between worlds? As an undergraduate at Notre Dame (not in architecture) I was struck by the similarity between the architecture students and the seminarians for the religious priesthood. Both dressed in black, both kept strange hours, both never really fit into the rah-rah campus life, both held prospects of poverty. Both were operating as people with vocations, where you do not choose a career path, it chooses you. Both were taking courses that were hardly likely to be of use when they decided to change majors.

Architects design temples and churches, which are sacred because society tells us they are. They can make them uplifting, sublime, unsettling, lofty, solemn, etc. They can take the predispositions of the visitors who are in search of the divine, and seek to ensure that the sensory environment contributes to and reinforces their expectations. The temple or church itself may house emotive power, but the assignment of divinity or otherworldliness must come from the client. Churches, we know, are very much a part of the everyday landscape. Anyone who is responsible for their upkeep, maintenance or repair knows that there is no divine intervention forthcoming. The bag of tricks relies heavily on structures, lighting and acoustics. If an architect seeks to sell services for building design by speaking of the buildings as sublime, sacred, spiritual, there are no police to enforce truth in advertising. Architects know, of course, that all magical or mystical ends are achieved by means that are utterly mechanical.

I attended a talk between Peter Eisenmann and Christopher Alexander many years ago. Alexander took the position that there are works of genius in the world, works that have embedded in them what it takes to move us. He said he would like to find the common thread among them, among works like Mozart’s operas and Chartres’ cathedral and Japanese traditional gardens, and certain pottery; he’d like to find what is behind or beneath or within works of genius. Eisenmann called that position preposterous. Alexander challenged him – what about Chartres? Eisenmann replied, ‘boring.’ He explained that he had gone there, had a passable visit to the cathedral, then stopped for a meal and wine at the restaurant right across from it. On later trips, he said, he stopped at Chartres for the wine at the restaurant, and didn’t bother with the cathedral. You can win points with insouciance, and Eisenmann always tries, of course. Years ago I went to Chartres with my wife. I was enthralled. Towards evening we stopped at the restaurant across from the west portal. It was overpriced. So we went a few blocks away and found a restaurant, good food, good wine. I asked myself why would anyone want to eat across from a cathedral except, of course, for the magical enticement of the cathedral itself. Hmmm, I think Eisenmann proved Alexander was right. There is indeed something alluring behind works of genius and every restaurant owner on earth knows it, and sets his prices thereby.

This concubine with whom I share the field of architecture never ceases to charm, and is full of surprises. I am kept on my toes, knowing that no algorithm or AI is going to deliver what genius has bequeathed us. As a building scientist, am I doomed to being a Sancho Panza, a one-dimensional squire to blind chance? If architecture is just such a pairing, well, Don Quixote and Sancho Panza make up the most endearing pair in all literature, so, I guess, I just have to make the best of it.

Leave a comment