We require attic ventilation in residential (non-low-slope) construction by code. And we’ve been venting attics for decades. Barroom chatter among builders will often leave a napkin on the table with an eave detail.

Venting carries an energy penalty? By now, you’ve probably thought the following:

- Up North, maybe, but in the South? In the summer?

- Even if there’s an energy cost to venting, it prevents moisture problems

- I need it for shingle warranty, and for the code inspector

- Say what you will, I’m venting.

In this paper I’ll make the case that on balance, North and South, venting carries an energy penalty. And by the way, it carries a resilience penalty too, but that’s for another paper. And moisture matters are for another paper too. Here, it’s all about energy.

Heating season. This is a no-brainer. Put your hand over a vent outlet when the furnace is on. The outgoing air will feel warmer than ambient. Heat is energy, and it is being lost. As they say in Latin—QED.

Cooling season For some, cooling season benefit is a no-brainer. Their argument goes like this:

- A vented attic is cooler during daytime than an unvented attic. (And it is, by tens of degrees.)

- Q = U×A×∆T. For the same R-value (R = 1/U), and for the same area (A), the heat flux (Q) goes up and down with ∆T across the insulation.

- Vented attics have lower ∆T, so lower heat flux, so lower energy use.

- QED. Venting provides cooling season benefit.

Then, like good researchers everywhere, we decided to test the benefit hypothesis. And like good researchers everywhere, we began with a literature search. This was back in the early 1990s. I found one study (lost however), by Doug Burch from the Buildings group at the National Bureau of Standards, now NIST. What Doug concluded was that cooling season energy use as a function of ventilation was indeterminate, was in the noise range, the results with and without ventilation were so close there was no conclusion. Couldn’t say one way or the other.

So we researched it at the lab building at the University of Illinois. We dedicated four bays all with the same ceiling insulation and the same truss framing. The four bays had alternating ventilation—1/150, none, 1/150, none. We started in late spring, and noticed right away that energy use was extremely sensitive to small differences in thermostat setting. So we invested in Vaisala sensors with factory settings, and computer control of cooling units. The temperature was much more uniform, but the humidity in the units varied. So we cleaned all the coils and finely tuned the coolant charge. We spent the summer sealing gaps, and minimizing door-open times and adding insulation between the bays. And in the end, the ranking of the cells in terms of energy use was—1/150, none, none, 1/150. All noise, no signal. No signal, no publication. This dog didn’t bark.

I came away thinking that ventilation is a wash in the cooling season. Why? What effect competes with ∆T benefit? Answer: air pressure. When the wind blows, an air pressure pulse is created in a vented attic that acts across the ceiling plane. That pulse is greatly attenuated without vent openings. No ceiling plane is perfectly airtight, so outdoor air and attic air is exchanged much more with ventilation. And that air carries both a sensible and latent energy penalty. How does ∆T and air pulsing play out? Probably differently day in and day out, from place to place. Who knows? Well, that’s what research is for.

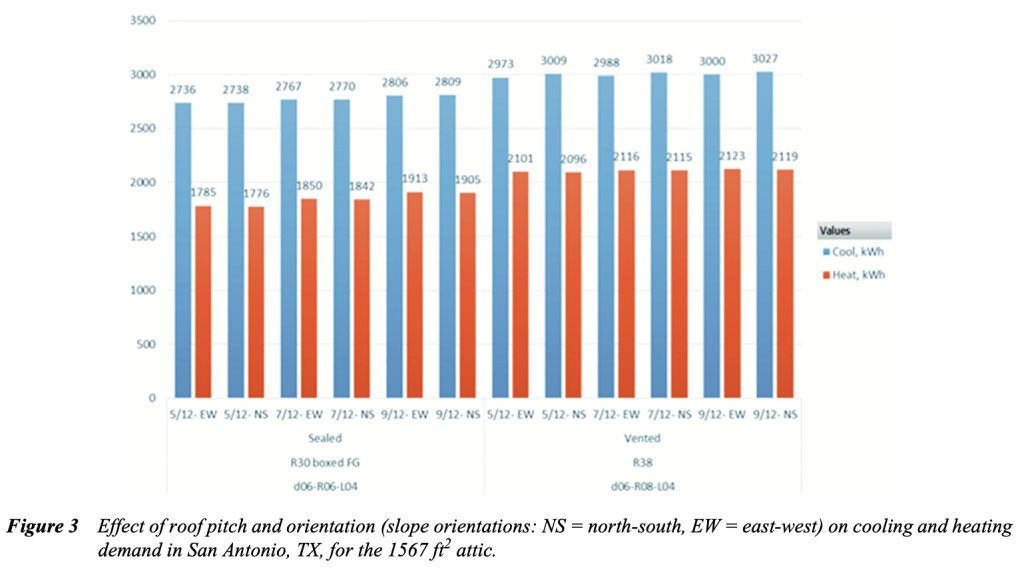

And if you want good research, you set researchers like me aside and turn to the A-team. That would be Achilless Karagiozis and Mika Salonvaara, and add Bill Miller who really knows Southern attic construction. The three of them published a paper for the 2016 Clearwater Conference on energy use in vented and sealed attics in Climate Zone 2A, which represents the Gulf Coast, with a focus on Houston.1 This was a modeling study, using a heat and moisture attic performance model developed by Ken Wilkes, the grandfather of such studies. The study looked at various parameters such as shingle emissivity, roof pitch and orientation, but our main takeaway is venting versus not venting of Southern climate attics. Modeling study outcomes depend entirely on the assumptions on which the study is based. One of the critical assumptions made in the Clearwater paper is the remaining leakage area in the sealed attic cases. Your assumptions may differ.

The vented attics use more energy pretty much across the board, and this despite the fact that the researchers decided to compare vented attics with more insulation to sealed attics with less. I cannot discern their reasons for this insulation choice. The findings can be shown in the four graphs they present, given below with captions from the original paper.

The conclusions of the paper include this: “The results show that unvented attics mostly perform better than standard, vented attics in the analyzed climates.” They don’t advise people to close up their vents. I don’t either, yet. They note “…sealed attics may need ventilation to provide acceptable moisture performance. Moisture performance was not part of this study…” Fair enough.

We have shown, I hope, that during heating season venting imposes a penalty, and during cooling season it’s kind of a wash, with a net effect being negative in term of energy. If ceilings are airtight, as they should be, then the ∆T benefit of summer venting becomes more apparent. The resilience penalty, which is suggested by air pulsing and how the outdoors enters into the attic, remains—but that’s for the next installment.

- Salonvaara, M., Karagiozis, A. and W. Miller. 2016. Annual Energy and Heat Flows in Vented and Sealed Attics— Parametric Study: Climate Zone 2A. Thermal Performance of the Exterior Envelopes of Whole Buildings XIII International Conference, Clearwater FL 2016. Paper no longer available on ORNL website. Presentation: https://web.ornl.gov/sci/buildings/2016/docs/presentations/principles/principles-05/Principles05_Paper137_Salonvaara.pdf ↩︎

Leave a comment