The starting point for building science is psychrometrics and the starting point for psychrometrics is water vapor pressure. Ever since the big bang, well a little later when matter condensed, our universe became composed of, among other things, atoms and molecules that have high speed and they collide elastically with one another. Any collection of fluid particles (atoms or molecules, in gases or liquids) will have varying activity or speed or energy of the particles, forming a probability (of speed) distribution. Higher the temperature, the greater the average speed.

The distribution is the Maxwell Boltzmann distribution. This is a three dimensional version of a chi-distribution, where all values are positive, since there are no negative speeds. There is no maximum speed either—the probability drifts toward zero for very high speeds. Here’s the equation and a graph showing the probability distribution. Energy is proportional to the square of the speed.

Water is a liquid at room temperature, they say. Well, there’s some water that is a gas at room temperature, and it’s the water at the water surface that has high enough energy to break the hydrogen bonds that keep the liquid together. The higher the water temperature, the greater the concentration of water vapor gas that is “sponsored” by the water surface. You can see that by comparing the high-energy quantity (area under the curve) of the most high-speed molecules.

When we have a fixed concentration of a gas we quantify it using pressure. Pressure is a lot easier to measure than counting molecules. In theory, it can be measured by creating a vacuum with a Torricelli barometer, then (somehow,) injecting a drop of water into the vacuum. If the barometer is, for example, a mercury barometer, then the difference in height between the vacuum and the vacuum + water vapor is the vapor pressure of the water vapor, at that temperature, in inches of mercury. In practice, technicians derive the vapor pressure from standard T/RH meters.

The vapor pressure above a water surface (an in equilibrium with that surface, at that temperature) is usually called the saturation vapor pressure. That distinguishes it from water vapor pressure that is less than the vapor pressure in equilibrium with a water surface. Saturation vapor pressure is rather rare in the air where we live, except in the upper atmosphere where cooling leads to condensation, and clouds.

There are equations for (saturation) vapor pressure over water of a given temperature. MY preferred is the Tetens equation.

P = 0.61078 exp( 17.27T / (T+237.3))

where T is in degrees C and P is in kiloPascals. The Wikipedia entry for vapor pressure of water provides a comparison of 8 different equations. This entry does not include the Hyland-Wexler coefficients which are used in the ASHRAE Handbook. These coefficients are ridiculously long, though they seem to provide estimates within a few hundredths of a percent, rather than within a few tenths of a percent with Tetens. Below is a Visual Basic equation that uses Hyland Wexler, using degrees Fahrenheit and giving output as psi. I use this function macro all the time.

Relative humidity is the ratio of the actual vapor pressure to the saturation vapor pressure at that temperature. This is fundamental. Relative humidity is very temperature-dependent.

Absolute humidity is any measure of air humidity that is unaffected by a change in air temperature. Dew point, humidity ratio and vapor pressure are examples of absolute humidity measures. Vapor pressure in a sample of air is unaffected by a change in air temperature, provided 1) that the overall air pressure is unchanged, and 2) the enclosure of the air sample is not affected by change in temperature—glass, for example, but not wood.

So, how do we use vapor pressure? Let me give a few examples.

Vapor pressure tends toward equilibrium in a space. If we find a space with two different values for vapor pressure, there is some non-equilibrating effect at work. This is the basis of moisture sleuthing. If two locations have different vapor pressures, then you can move the instrument with higher vapor pressure around in the space and find the source of moisture where the vapor pressure is greatest.

Care to estimate the air-leakiness of a building? We can do this where there is no strong moisture source.

Imagine we measure T and RH every hour, we convert this to vapor pressure, inside the building and outside the building. Now imagine a building with one—fully mixed—air change per hour. Imagine the building taking on a volume of outdoor air equal to the building volume, thus doubling the air volume inside (the building inflates), mixing that air, then discharging that extra volume (building deflates) at the end of our hour-long measurement interval. In that case our building now has half of its air coming from the previous air volume inside (“old air”) and half the air coming from outside (“new air”). And because the ventilation volume was exactly one building volume, and our measurement interval was one hour, the air exchange rate is one air change per hour. The resulting ratio of “new air” to “old air” is 1 to 1 or 1.

If we had added three volumes instead of one in the course of the hour we would say it had three air changes per hour. The resulting ratio of “new air” to “old air” is 3 to 1. If we had added only a half a building volume, then it has half an air change per hour. And the newair/oldair ratio is 0.5 to 1.

Note the “fully mixed” requirement. We can also imagine a strange house subject to a strange wind, which blows against one side of the house, and like a piston, exchanges all the original house air with new outdoor air. The resulting air would have very different qualities compared to our building with the mixing requirement.

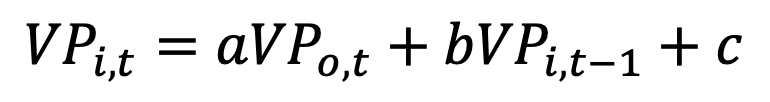

We have indoor and outdoor vapor pressure values, taken every hour (time t in the equation below). We may use the vapor pressure as a tracer gas, that distinguishes old from new air. We can plot the data in two columns, and do a linear regression to estimate interior vapor pressure (VP) from outdoor, using two inputs. The first input is obvious: the concurrent outdoor VP—new air. The second input to use is the previous reading of indoor VP—old air. The regression result will be:

Since all of the values for VP are close to one another, we may expect a + b + c to equal close to a value of 1. If the building really does have no other moisture sources, then the value of c should be 0 or close to it. So a is the new air fraction and b is the old air fraction and air changes per hour is a / b. Leave your blower door at home, two T/RH sensors are a lot smaller and cheaper. On second thought, don’t stop making blower door measurements.

Visual Basic function for vapor pressure, I-P units, using Hyland-Wexler coefficients:

Function VaporPressure(Temperature, RH)

‘convert degrees Fahrenheit to absolute (Rankine) temperature

tt = Temperature + 459.67

if RH>1 then RH=RH/100

‘allows RH to be entered as a percent (<=1) or a number <=100

‘constants over ice from ASHRAE Handbook of Fundamentals, Chapter 6

zz1 = -10214.16462

zz2 = -4.89350301

zz3 = -0.00537657944

zz4 = 1.92023769E-07

zz5 = 3.55758316E-10

zz6 = -9.03446883E-14

zz7 = 4.1635019

‘constants over water

zz8 = -10440.39708

zz9 = -11.2946496

zz10 = -0.027022355

zz11 = 1.289036E-05

zz12 = -2.478068E-09

zz13 = 6.5459673

If Temperature < 32 Then

lnSVP = zz1 / tt + zz2 + zz3 * tt + zz4 * tt ^ 2 + zz5 * tt ^ 3 + zz6 * tt ^ 4 + zz7 * Log(tt)

Else

lnSVP = zz8 / tt + zz9 + zz10 * tt + zz11 * tt ^ 2 + zz12 * tt ^ 3 + zz13 * Log(tt)

End If

svp = Exp(lnSVP)

VaporPressure = svp * RH

‘Output is in psi

End Function

Leave a comment